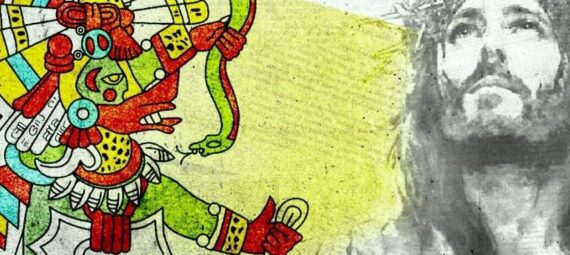

The connection between Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent deity of Mesoamerican cultures, and Jesus Christ has been a topic of much discussion, particularly in colonial and post-colonial scholarship. The idea that Quetzalcoatl may be a precursor or equivalent to Christ is not a recent invention. It first emerged in the early period of Spanish colonization when Mendicant friars and missionaries sought to convert the indigenous populations of the Americas to Christianity. This connection, however, is an oversimplification that disregards the deep cultural, historical, and religious differences between the two figures.

In this blog post, we will explore why Quetzalcoatl is not Jesus Christ, analyze the motivations behind early Spanish preachers in making such associations, and unpack the indigenous traditions that predate both the arrival of Christ and the Aztec civilization. Through an exploration of myth, history, and colonialism, we will also examine how the Mesoamerican world borrowed and integrated various elements from earlier cultures, including the Maya, the Olmec, and the Quiché.

The Myth of Quetzalcoatl: More Than Just a Feathered Serpent

Quetzalcoatl, whose name translates as “Feathered Serpent,” was one of the most significant deities in the pantheon of the Aztecs, the Mexica people. However, the god did not emerge from the Aztecs alone but was part of a much older Mesoamerican religious tradition. The earliest representations of Quetzalcoatl can be traced back to the Olmec civilization (around 1200 BCE to 400 BCE), and his attributes were further developed and refined by later cultures like the Maya and the Toltecs.

In the context of the Aztec religion, Quetzalcoatl was associated with creation, the wind, knowledge, and life itself. He was seen as a benefactor to humanity, a god who imparted knowledge about agriculture, the calendar, and writing. In fact, Quetzalcoatl’s mythos is deeply connected with the cycles of life and death, as well as with the concept of resurrection and renewal. However, Quetzalcoatl’s role as a divine figure is not simply a narrative of death and rebirth like that of Christ but rather a complex, multilayered mythos that reflects the agricultural and cosmic cycles of the Mesoamerican world.

Quetzalcoatl was not, as some would argue, a singular figure destined to redeem humanity in the Christian sense. His stories—while involving departure and return—are tied to the cyclical nature of time, rather than the linear journey of salvation represented in Christianity. In fact, Quetzalcoatl’s mythology often involved him leaving or withdrawing from the world as a means of ensuring that the cycles of life could continue.

The Influence of the Maya, Olmec, and Quiché Cultures

To fully understand Quetzalcoatl, it is essential to recognize the cultural borrowing that occurred across Mesoamerican civilizations. Although Quetzalcoatl became most prominent in Aztec cosmology, his symbolic predecessors can be found in earlier civilizations such as the Olmecs and the Maya.

The Olmecs (c. 1200 BCE to 400 BCE) are often credited with the earliest representations of a feathered serpent deity. The Olmec civilization, known for its colossal stone heads and sophisticated artistic traditions, also depicted a serpentine figure associated with fertility, rain, and the life force. This serpent was not the same as the Aztec Quetzalcoatl, but it laid the foundation for later interpretations of similar deities in other Mesoamerican cultures.

Later, the Maya—who flourished from the 3rd to 10th centuries CE—had their own feathered serpent deity called Kukulkan. Kukulkan shares many attributes with Quetzalcoatl, including associations with the wind, creation, and the heavens. However, Kukulkan’s mythological significance was also rooted in the Maya’s unique worldview, which was different from the Aztec perspective. While both deities were symbols of knowledge, renewal, and divine influence, their roles and the meanings attached to them were deeply embedded in each civilization’s unique religious context.

The Quiché, a Mayan-speaking people, also had a tradition of a feathered serpent deity, which played a significant role in the Popol Vuh, the sacred text of the Quiché Maya. The deity represented by the feathered serpent in the Popol Vuh is associated with creation and cosmological order, similarly to Quetzalcoatl’s role in Aztec religion. This underscores the broader Mesoamerican tradition of serpent-like deities associated with life, wisdom, and the forces of nature—long predating the arrival of Christianity.

The Role of Spanish Mendicant Preachers: Motivations Behind the Connection

The connection between Quetzalcoatl and Jesus Christ first emerged in the early days of Spanish colonization, particularly with the work of mendicant friars such as Bernardino de Sahagún and Diego de Landa. These missionaries were charged with converting indigenous populations to Christianity, and part of their strategy involved reinterpreting native beliefs through a Christian lens.

One of the key reasons why early Spanish missionaries sought to link Quetzalcoatl to Jesus Christ was to facilitate the process of conversion. By drawing parallels between the two figures, the missionaries hoped to show the indigenous peoples that their gods were merely distorted versions of the Christian god. This method of “cultural assimilation” was a common tactic during the period of religious and cultural conquest. It allowed the Spanish to position Christianity as the “true” religion while simultaneously validating the indigenous belief systems to a degree.

A prominent example of this is the theory put forward by some Spanish chroniclers that Quetzalcoatl’s return would coincide with the arrival of the Spanish. The idea was that the Aztecs, based on their own prophecies, believed that Quetzalcoatl—who had once departed from the world—would return to reclaim his throne. Some early missionaries, most notably the Dominican friar Diego de Landa, seized upon this belief and claimed that Quetzalcoatl’s return was a sign that the Christian god had come to replace the old gods of the indigenous people. This myth of Quetzalcoatl’s return played a significant role in the Spanish justification for conquest, as they believed that their arrival was divinely ordained.

However, this Christian interpretation of Quetzalcoatl is problematic for several reasons. Firstly, it oversimplifies the polytheistic nature of Aztec religion, where Quetzalcoatl was just one of many deities in a complex pantheon. Secondly, it disregards the deep cultural meanings attached to Quetzalcoatl and other Mesoamerican gods, who were not seen as personal saviors in the same way that Jesus Christ was.

Borrowing and Syncretism in Mesoamerican Religions

In addition to the cultural borrowing between the Olmecs, Maya, and Aztecs, it is essential to recognize the phenomenon of syncretism in Mesoamerican religious traditions. Over the centuries, these civilizations integrated and adapted beliefs and symbols from each other, resulting in a rich tapestry of religious ideas that transcended individual cultures.

The feathered serpent motif, for example, was a common thread woven through various Mesoamerican religions. While Quetzalcoatl’s version was most clearly articulated by the Aztecs, it was part of a broader religious framework that drew on older traditions and myths. The Maya’s Kukulkan, the Olmec’s serpent deity, and the Quiché’s feathered serpent all share similar symbolic attributes, including wisdom, creation, and fertility.

This syncretism reflects the way in which Mesoamerican societies did not operate in isolation but rather engaged in a dynamic exchange of religious and cultural ideas. These ideas were not static but evolved over time, allowing each civilization to reinterpret them in ways that were relevant to their own cosmological views and societal needs.

Quetzalcoatl and Jesus Christ—Two Separate Realities

While early Spanish missionaries sought to equate Quetzalcoatl with Jesus Christ, such a comparison is neither historically accurate nor theologically sound. Quetzalcoatl’s role in Mesoamerican religion was far more complex and rooted in indigenous traditions that predated the arrival of Christianity by centuries. His mythological significance as a creator god, bringer of knowledge, and symbol of renewal bears little resemblance to the Christian concept of salvation, atonement, and personal redemption that Jesus represents.

The association between Quetzalcoatl and Christ was motivated by the colonial desire to assimilate indigenous religious beliefs into Christianity, a strategy that served the Spanish colonizers’ objectives. However, it disregards the distinctiveness of Mesoamerican religious thought and the richness of the cultural exchanges that took place between the various civilizations of the Americas.

Thus, Quetzalcoatl should be understood within the context of Mesoamerican religion, and while there are certainly similarities between various cultural traditions, these similarities do not imply equivalence. Rather, they reflect the diverse ways in which different peoples sought to understand the world around them through myth, ritual, and divine beings.

Sources:

- Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: General History of the Things of New Spain.

- Diego de Landa, Yucatan before and after the Conquest.

- Michael E. Smith, The Aztecs: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2012).

- David Carrasco, Quetzalcoatl and the Aztec Religion (University of California Press, 1983).

- Enrique Vela, The Olmec and the Origins of Mesoamerican Civilization (University of Oklahoma Press, 2004).