Many individuals unfamiliar with the intricacies of Mayan linguistics often hold the misconception that Mayan constitutes a singular, cohesive language that was prevalent across Mesoamerica. This assumption, however, does not hold true. In present-day Guatemala, there exist 22 officially recognized Mayan languages, each distinct in its own right. Moreover, Spanish is spoken alongside two other indigenous languages: Garífuna and Xinca. Garífuna, an Arawak language originally rooted in the Amazon basin, found its way to Central America via the transatlantic slave trade from the Caribbean. Conversely, Xinca stands as a language isolate, confined to a mere two hundred speakers in the Santa Rosa and Jutiapa departments, placing it on the brink of extinction.

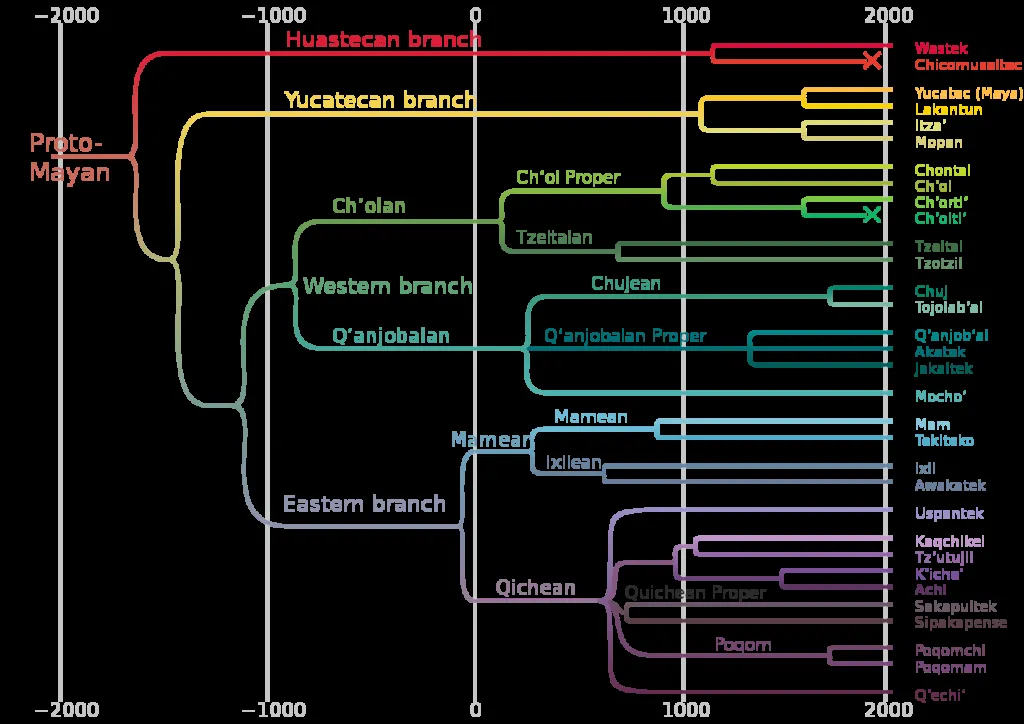

Mexico hosts an additional eight Mayan languages, contributing to a total of 30 currently spoken Mayan languages. These languages are typically classified into the following branches: Yucatecan, Huastecan (Wastek), Chʼolan–Tzeltalan, Qʼanjobʼalan, Mamean, and Kʼichean.

Proto-Mayan, believed to have been spoken approximately 5000 years ago, is a subject of ongoing debate and intriguing hypotheses suggest early influences from Mix-Zoque languages on this ancestral tongue. Following the classification framework established by Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman, the initial divergence took place circa 2200 BCE. During this period, Huastecan separated from the core Mayan group as its speakers migrated northwest along the Gulf Coast of Mexico.

Afterward, the progenitors of Proto-Yucatecan and Proto-Chʼolan underwent a division, venturing northward into the Yucatán Peninsula. Simultaneously, the western branch migrated southward, settling in regions currently occupied by Mamean and Quichean communities. As the speakers of proto-Tzeltalan later detached from the Chʼolan cluster and journeyed south to the Chiapas Highlands, they encountered individuals who spoke Mixe–Zoque languages.During the Classic and Post-Classic periods of the Mayan civilization, three Mayan languages became very important to providing valuable insights into their culture: Ch’olti’, K’iche’, and Yucateca.

During the Classic period, the major Mayan branches embarked on a process of diversification into distinct languages. By this era, the division between Proto-Yucatecan, situated in the northern Yucatán Peninsula, and Proto-Chʼolan, located in the southern regions encompassing the Chiapas Highlands and Petén Basin, had already taken place. These two variants were both documented in hieroglyphic inscriptions from Maya sites of that era and are commonly referred to as the “Classic Maya language.”

Although a single prestigious language predominated in the majority of hieroglyphic texts, evidence has emerged of at least three distinct Mayan varieties within the hieroglyphic corpus. These include an Eastern Chʼolan variety, observed in texts written in the southern Maya area and the highlands, a Western Chʼolan variety that diffused from the Usumacinta region starting from the mid-7th century onwards, and a Yucatecan variety evident in texts originating from the Yucatán Peninsula.

Therefore, most of the hieroglyphs that are produced have an underlying language of either Eastern Chʼolan, Western Chʼolan, or Yucatecan. These three varieties give us great insight into the classical period through the hieroglyphs that are present in the archaeological record.

The other language that became important is Ki’che’ in the eastern branch of the Mayan language family. This language was spoken in the highlands of Guatemala in the Cuchumatan mountain range. This language is important as it was the K’iche’ people who wrote the Popol Wuj. This has given considerable insight into not only the origin myths of the Ki’che’ people but also their lineage and history.

Although these languages were important in the Mayan area they certainly were not the only languages spoken. Influence from other cultures was very strong. In the Pre-Classic and early Classic periods, there was a strong influence from Mixe-Zoque languages. This language family is believed to be, at least some evidence would suggest, that it was spoken by the Olmec(to what degree is still debated). There is also evidence to suggest that Mixe-zoque speakers were involved in the initial stages and subsequent development of the Maya hieroglyphic writing system.

I mention the Mixe-Zoque language family despite it not being a Mayan language because this language group is intricately woven into the tapestry of the Mesoamerican linguistic region. Historical indications suggest that the Olmecs likely employed this language family to some extent. The association with the La Mojara Script (Epi-Olmec) further bolsters this connection. Moreover, evidence partially supports the notion that Teotihuacan, to a debatable extent, embraced Mix-Zoque as a spoken language. Additionally, as previously noted, signs of Mixe-Zoque presence can be traced within Proto-Mayan and early hieroglyphic Mayan writing. Hence, any discourse about the Mayan language family necessitates an exploration of the Mixe-Zoque language family, given its significant proximity to the Mayans and apparent influence on their linguistic development in the Pre-Classic and Formative periods.

In summary, exploring the evolution and changes in Mayan languages offers a fascinating glimpse into how language and culture have transformed over time. The roots of these languages go way back to Proto-Mayan, which is still debated and believed to have connections with Mix-Zoque languages. Lyle Campbell and Terrence Kaufman’s classification helps us understand when these languages began to separate. The divisions of Huastecan and Mayan branches led to the creation of various languages that contributed to shaping the diverse Mayan civilization.

Among these language developments, some Mayan languages have been crucial for understanding history. Ch’olti’, K’iche’, and Yucateca were especially important during the Classic and Post-Classic periods. They revealed aspects of culture and history through their hieroglyphic writings. The K’iche’ language, in particular, originating in the Guatemalan highlands, gave rise to the renowned Popol Wuj, unveiling the stories and lineage of the K’iche’ people.

While these languages are key to understanding the Mayan world, it’s also important to recognize the influence of other cultures. Mixe-Zoque languages have left their mark during the Pre-Classic and early Classic periods, showing how different languages and cultures interacted. This mixing, which might involve the Olmec civilization, likely contributed to the development of the Maya hieroglyphic writing system. It all underscores the intricate connection between language, history, and cultural exchange in the captivating story of the Mayan linguistic journey.